Stitching Temporalities

The following article was first published by The Seen in September 2018.

Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions 1965– 2016 collects nearly 300 individual works of the artist’s work, beginning with late-adolescent paintings, to more recent reflections on the Black Lives Matter movement. What emerges from this assembly is an ongoing interrogation of the frameworks that shape everyday experience. By employing performance, video, writing, sculpture, and photography, among other materials, Piper explores the capacity for an individual to challenge cultural, ideological, and logical frameworks through her unflinching address of xenophobia, racism, and sexism.

It is perhaps for this reason that Piper’s early LSD paintings are given such prominence, appearing both at the beginning of the exhibition and regularly referred to in the exhibition’s collected essays. Regardless of the objective merit of these paintings-as-paintings, the LSD works function as a point of origin for the show and its subsequent trajectory. These paintings represent a record of Piper’s consciousness as it was disrupted within the context of a personal and social movement. The real moment of interest, however, occurs not in the LSD paintings themselves, but rather the way they pivot into an ongoing series of spare, geometric language studies from 1968, which “attempt to make form as transparent as possible, to limit its parameters, to eliminate all that is unnecessary, to opt for mediums that are intrinsically uninteresting,”1 essentially proving through a series of visual exercises that form is second to concept.

At just twenty years old, Piper found herself at the vanguard of Conceptual Art, producing works on paper that employed geometric grids and language to map, without fuss, a location. She was featured in some of Conceptual Art’s most significant North American exhibitions, and worked closely with well-known others in the field, such as Sol LeWitt, her downstairs neighbor.2 In a 1968 work, Here and Now, for example, Piper used sixty-four sheets of paper, each one gridded into equal eight by eight squares. From left to right, top to bottom, she sequentially identifies each box by inscribing its relative location, for instance: “HERE: the sq/ uare area i/ n 3rd row f/ rom bottom,/ 3rd right side.” Here, one sees a blur between philosophic investigations and aesthetic production—a blur that continues to echo throughout Piper’s work in increasingly sophisticated and nuanced ways. She characterized this effort as “the most direct method for expressing a concept so that viewers would understand the work as she did.”3 Even in these drier studies, and unlike her peers, Piper remained interested in politics. “Piper learned that pitting a concept against its verbal and material forms questioned each other.”

At just twenty years old, Piper found herself at the vanguard of Conceptual Art, producing works on paper that employed geometric grids and language to map, without fuss, a location. She was featured in some of Conceptual Art’s most significant North American exhibitions, and worked closely with well-known others in the field, such as Sol LeWitt, her downstairs neighbor.2 In a 1968 work, Here and Now, for example, Piper used sixty-four sheets of paper, each one gridded into equal eight by eight squares. From left to right, top to bottom, she sequentially identifies each box by inscribing its relative location, for instance: “HERE: the sq/ uare area i/ n 3rd row f/ rom bottom,/ 3rd right side.” Here, one sees a blur between philosophic investigations and aesthetic production—a blur that continues to echo throughout Piper’s work in increasingly sophisticated and nuanced ways. She characterized this effort as “the most direct method for expressing a concept so that viewers would understand the work as she did.”3 Even in these drier studies, and unlike her peers, Piper remained interested in politics. “Piper learned that pitting a concept against its verbal and material forms questioned each other.”In Utah-Manhattan Transfer (1968) for instance, she takes a map of Manhattan and places it, to scale, on a map of the Dugway Proving ground in Utah—a site where 6,000 sheep living on ranches around a US Military base died the same year, allegedly because of chemical warfare testing the government was conducting in secret. Utah- Manhattan Transfer’s simple, visual correlation between locales uses the trusted map-format to ask viewers if other geographic locals might be equally vulnerable to military accident. In so doing, she maps language on a page in order to locate the viewer in abstract space—a space that nevertheless designates a national, political, and geographical framework. As art historian John P. Bowles states, “What is at stake in Piper’s self-reflexive cartography is nothing less than the social construction of the self.”5

Piper translates this same—call it an echolocation— strategy into street performances via a series of seven works she called Catalysts, between 1970 and 1973. In these semi-documented, largely solitary events, the artist would walk down the street in a sweatshirt soaked in wet paint with the statement “WET PAINT” inscribed across it, ride the bus with a towel stuffed in her mouth, or enter a bookstore wearing stinking clothes. By deviating from seemingly benign social conventions of comportment, she begins to use her own body as a locating device. Challenging an otherwise pervasive sense of normality, “Piper’s break with strictly conceptual practice was not only about moving away from making objects; it was also about the world crashing in on [her] hermetically indexical practice.”6

Events such as Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia, the Jackson State and Kent State shootings, the Women’s Movement, and the closing of CCNY inspired this change in Piper’s development driving her interest beyond of the codified gallery context. “Mostly,” Piper writes of this period, “I did a lot of thinking about my position as an artist, a woman, a black; and about the natural disadvantages of those attributes.”7 By eliciting the surprise and potential discomfort of others, she demonstrates how the public inadvertently reasserts and thus reinforces conventions in social experience. As such, her ad hoc audience—those seated around her on the bus, for example—is catalyzed, becoming essential members of the performance precisely because they define the context that charge Piper’s actions with meaning. As she put it, “I feel as though a lot of the work I am doing is being done because I am a paradigm of what the society is.”8

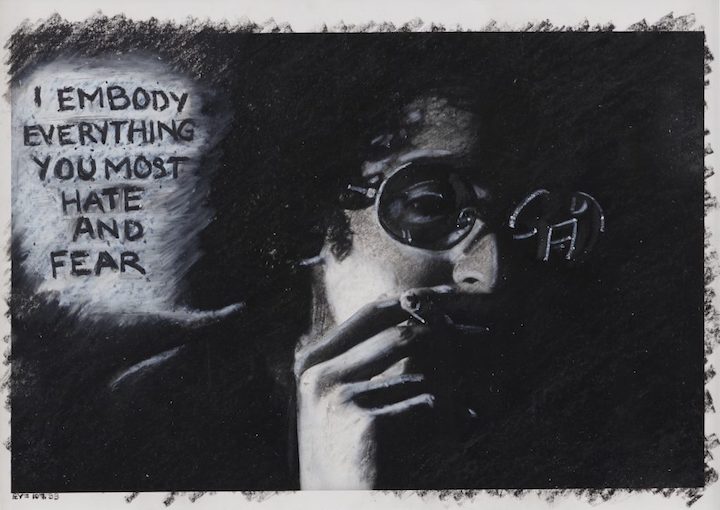

Piper’s Mythic Being (1973) furthers this experiment of disruption via a developed gender bending persona. In answer to the question, “What does a ‘static emblem of alien confrontation’ wear?”9, Piper dressed herself in reflective sunglasses, a moustache, an Afro wig, and the performed affectations of a man—a swagger, for instance. In his periodic and public appearances, the Mythic Being further embodies and extends preceding computations of Piper’s works on paper—as though the effort to draw equivalencies on the grid no longer served her. In a moment of energy, and perhaps even frustration, we can imagine the artist taking to the streets to experiment there, with her body, and show the ways that more pointed expectations of race and gender might gird and flex against alternate persona.

Writer Jörg Heiser cautions us against assuming that Piper is solely reacting to her own racial and gendered identity: “To identify Piper’s work as predominantly, even solely, as political art is to designate as causative that which is effected; it is to say that her political agency, defined by her social identity, causes the art, instead of that her experimentation and analytic explorations—of how individuals interact, of how racist or sexist behavior manifests itself—effect political agency… This misapprehension proves Piper’s points about the distortions that stereotypes produce.”10 In fact, Piper’s attention to the frames in which we reside gives her the agency to interrupt them, make them malleable, and demonstrate the way entrenched ideologies around difference are paradigmatic to society, not essential conditions of human experience. Race and xenophobia are central themes to work because she recognizes both their importance and their arbitrary assignment, as enforced by a societal point of view. Mythic Being is a form that allows her to take on a different set of preexisting opportunities and limitations that would otherwise be inaccessible.

In a later room of the exhibit, the artist deconstructs her own body with What Will Become of Me, (1985–ongoing), featuring two typewritten, framed texts flanking a single blue shelf with fourteen jars containing an ongoing collection of hair and fingernail shavings. In the first text, Piper states that “1985 was a bad year;” her father was diagnosed with cancer, her philosophical work was dismissed as “baffling,” she was denied tenure, and her marriage deteriorated. In the last line of this text, she writes “I felt sure that if I could hold myself together long enough to escape Ann Arbor, I’d be alright.” The subsequent jars enact a literal “holding together” as the jars literally contain remnants of her body; the final framed letter confirms that the entire piece plus her cremated ashes will, upon her death, go to the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Here too, Piper interrogates the frame of her body as it intersects with larger institutional frameworks—whether those of a university, a museum, family, or marriage, and whether her personal effects are philosophical academic writings, art works, or bodily remains. What Will Become of Me thus reminds viewers of a basic and even generic materiality in this odd equivalence.

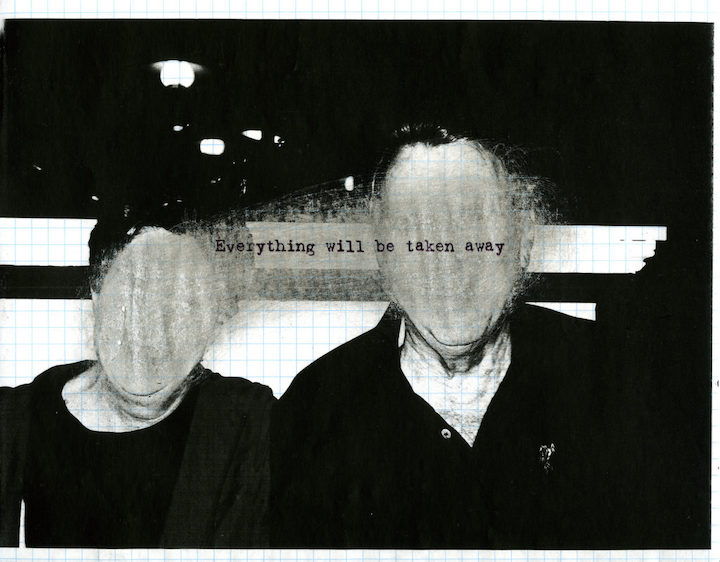

As the exhibition framework of A Synthesis of Intuitions continues, the audience’s implication within it expands. That expansion is perhaps most evident in The Humming Room (2012), a piece originally commissioned for Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Do It series. The room occurs two-thirds of the way through the show; audience members must pass through the room in order to continue, linearly, onto later works on display. According to a free-standing museum sign, The Humming Room requires visitors to hum while passing through the space and—at least when I was there—are joined and encouraged by the attending guard. The Humming Room is joyful, while other contemporary works remind the viewer of a more sobering complicity: works like Imagine [Trayvon Martin] (2013) where a photolithograph is divided into crosshairs that overlay a faded and barely visible portrait of Trayvon Martin, with the typewritten courier text in the bottom right hand corner, “Imagine what it was like to be me.” Or a series of photographs entitled Everything Will Be Taken Away (2003– ongoing), where subjects in personal photographs have their faces erased. The show concludes with a performative work, The Probable Trust Registry (2013), a series of desks where viewers check in and agree to a series of promises like “I, the undersigned, hereby certify that I will always (absent uncontrollable Acts of God) do what I say I am going to do,” and in so doing, enter a registry and effectively become data.

Although Piper may have abandoned the project of early abstraction, her study of the grid remains equivalent to her study of the material body—the way the body frames (or contains) the subject, for instance, imposes political associations as a social consequence of its visual attributes. Her work consistently bends those associations of race and gender, demonstrating how malleable, and therefore subjective, they are.

It is as though the spirit of the Mythic Being continues to aid Piper’s own ability to pass between worlds and expectations, highlighting the fragility of convention and moirés as she goes. As Cornelia Butler points out in her curatorial essay, “The occasion of Adrian Piper’s fifty-year retrospective exhibition lands in the United States at a moment when the national conversation about race, identity, immigration, and the golden rule are singularly and urgently unfolding in real time, embroiled in a cultural mood and climate of fear that is being fed from the top ranks of government.”11

For this reason, the one failure of the exhibition is that it exhausts the presentation of Piper’s work in a single site of the museum. Indeed, it is the first time MoMA has dedicated its sixth floor to a single artist, but I would argue that the work’s uncanny contemporary resonance is, at least partially, neutered by its institutional setting. Given Piper’s ongoing interest in interrogating frameworks beyond the scope of art institutions, one cannot help feeling that MoMA’s gesture is incomplete without a presentation of some of these works in public space. Imagine, for instance, the power of encountering the video installation Cornered (1988) in an Amtrak Train Station—a video piece where Piper wears a pearl necklace to inform the viewer of her mixed heritage, flanked on either side by two variations of her father’s birth certificate: one identifies him as white whereas the other identifies him as octoroon. “If I don’t tell you who I am, then I have to pass for white,” she says, later concluding her direct address with the question: “So how do you propose we solve it? What are you going to do?” Or, conversely, if MoMA could have taken out a national billboard campaign to enact the 1987 billboard mockup, Think About It: a sign featuring the collage of a crowd with overlaid text that reads “OUR FAMILIES HAVE BEEN INTERMINGLING FOR DECADES THINK ABOUT IT.” Imagine the impact this provisional sign might have on today’s roadways—what happens when these temporalities are stitched together?

There is a false sense of security in MoMA supplying these works for exhibition—allowing us, the audience, a sense of historical distance, as though the social conditions we currently inhabit have somehow improved if we can canonize an artist like Piper, someone who fearlessly and calmly addresses the curious impositions we put upon one another. This however, is false. The stress of racial relations, gender equality, and class is terribly enflamed, to such an extent that President Obama is recorded wondering if he came ten or twenty years too early.12 Piper staunchly believed that art could change society. Experiencing her work outside of the museum could further amplify its resonance—between the national conversation today, and the national conversation from which the work was originally born.

Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions ran at the Museum of Modern Art from March 31–July 22, 2018.