HYPER-PLURALITIES FOR A NEW BECOMING: THE EXHIBITED BODY IN CONTEMPORARY ART

The following article was originally published by Artslant on January 16, 2015.

“The body is always a body that is an unfinished entity.” —Lisa Blackman, The Body (Key Concepts), Berg, 2008

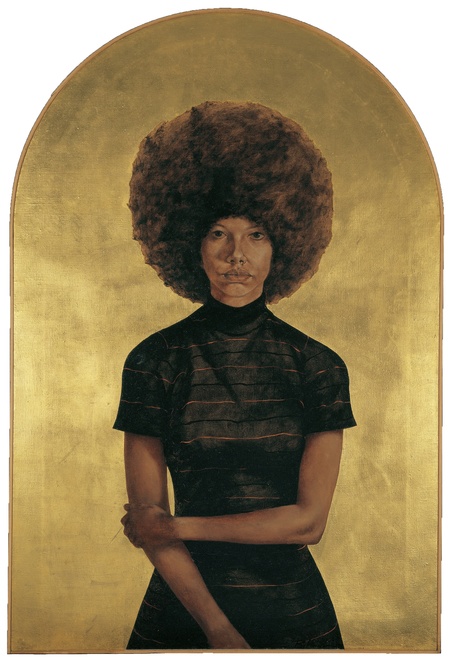

“We have a whole history of representation in which the black body was not the privileged body,” Kerry James Marshall said in an interview a few years ago. “So there was no crisis of representation for me, because the black figure is underrepresented.” Marshall has patiently, and masterfully installed black figurative paintings in predominantly white institutions for his entire career; this past fall he had a solo show at David Zwirner Gallery in London—what Culture Type hailed as one of six must-see exhibitions during Frieze. He is not alone, however. The figure has been steadily inching its way back into popular focus, and not just any figure either—it’s the plurality of figures that challenges a single ideal of what a body should be.

In 2014 Kara Walker’s A Subtlety: or the Marvelous Sugar Baby drew some 130,000 viewers while installed at the now defunct Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn. Along with its installation came a wave of controversy inspired by the white public’s tendency to take suggestive and derogative selfies beside the 30-ton sugar sphinx’s vagina. (A related lecture will take place this February at the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality at the University of Chicago.) The body, and tension around racial identity in the US became an international priority as multiple cases of the police brutality captured media attention. One response came by way of Claudia Rankine’s 2014 book, Citizen. A finalist for the National Book Award, it carries an image of David Hammons’ In the Hood on its cover. “Even as your own weight insists / you are here,” Rankine writes, “fighting off / the weight of nonexistence. // And still this life parts your lids, you see / you seeing your extended hand…”

Historically marginalized figures challenge a tide of entrenched policies and networks that have alienated many in favor of a singular, coherent narrative, a single, coherent body. Wangechi Mutu’s tremendous traveling solo exhibition, organized by the Nasher Museum, used fantasy and hybridity to celebrate the figure. Meanwhile Jacolby Satterwhite continued his own creative trajectory through multisexual transpersonal landscapes at OHWOW gallery in Los Angeles. How Lovely Is Me Being As I Am featured several C-Print photographs, sculptures, and a six-channel video from his Reifying Desire series, in which the body becomes an intersection of material, digital, erotic, and personal forces. These bodies are not simply material or psychological, but rather complex assemblages with fluctuating interior and exterior bounds—like the skin itself, a porous membrane between inside and outside, acting as both boundary and passage. Or to quote Alexander G. Weheliye’s Habeas Viscus (Duke Univeristy Press, 2014) “because to fully inhabit the flesh might lead to a different modality of existence.”

Following suit, Chicago’s MCA fills one half of its first floor with Body Doubles, an ongoing group show that “recognizes that the body is not fixed, but is rather in a perpetual state of flux and transformation.” Critic Matt Morris curated a related group show Effeminaries, at Western Exhibitions in the West Loop. Amid video, shirt paintings, a floor sculpture, and wonderful loose magazine pages of Joel Parsons’ “Crushes,” are three Greg Ito paintings: nude, beige, and brown—minimalist except for two pieces of jewelry adorning each picture.

Greg Ito, (from left to right) the one that got away, as deep as out love, the comedown is real, all three: 2014, acrylic, muslin, velour, jewelry, wood, 22 x 36 x 1 3/4 inches; Courtesy of the artist and Western Exhibitions, Chicago

Revisiting her Creative Time installation in a different context, Kara Walker’s current solo show at Sikkema Jenkins (aptly called Afterword) “elaborates on the creation and aftermath of Kara Walker’s monumental installation at the Domino Sugar Refinery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn this past summer.” Through a small model and sketches of the Sugar Baby on paper, the larger-than-life figure from the summer is seen coming into existence by way of Walker’s thinking hand. You see Walker working out and developing the Sugar Baby. The original molasses boy sculptures remain attendant, and a hand of the original sphinx sits on the gallery floor as well—like a relic from ancient times, one side shorn hard with marble-like ridges.

At the New Museum, Night and Day, Chris Ofili’s first major museum solo in the US, will be on view until February 1. According to the New York Times, these “paintings will not let us be.” And thankfully so, for they trouble dominant cultural tendencies. Continuing into 2015 Wiels in Brussels features Body Talk: Feminism, Sexuality and the Body in the Work of Six African Woman Artists. In Austin, Texas, The Blanton Museum of Art is hosting a traveling group show about the Civil Rights Movement that opens this February. And reminding us again of the global conversation between international bodies, cultures, and policies, the Iranian-American artist, Shirin Neshat’s solo exhibition, Facing History, opens at The Hirshhorn in D.C. this May.

A friend recently asked why art wasn’t more politically engaged. I feel it is. More unblinking and fearless and calm than ever. These works come from a calculated, and wonderfully dangerous place. A place of love and ferocity, carving out as they do a platform upon which “you see / you seeing your extended hand.”