Kerry James Marshall // Profile of the Artist

“We are not, as we sometimes like to imagine, independent thinkers with our own unique & groovy style of cognition: we have in fact inherited a narrow repertoire of prefab concepts, and we find ourselves thinking as thinking things on highly ramified architectonics of ideas, and along deeply grooved paths of thought-action.” [1]— Karen Houle

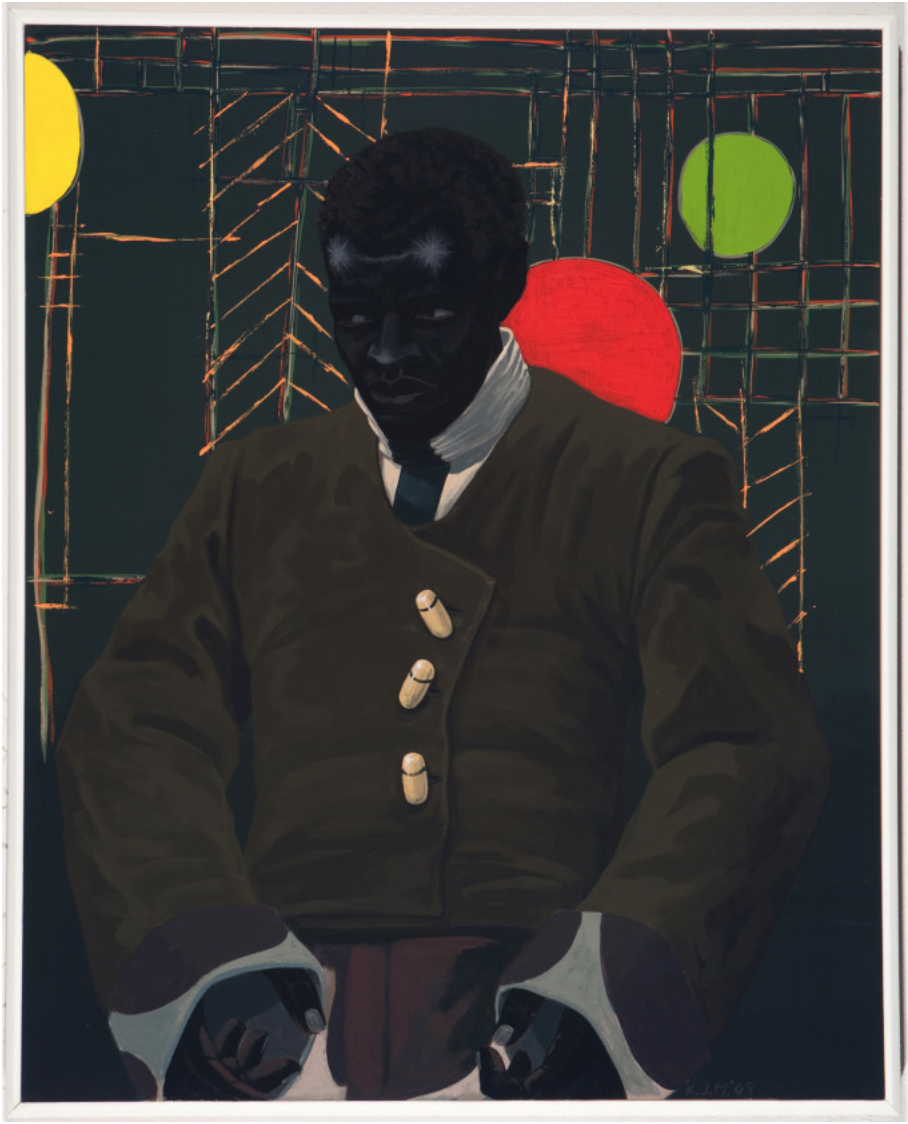

Kerry James Marshall has consistently taken the canon of art history and the myriad network of art institutions it has occupied to task for their grave omission of blackness. His first retrospective, Mastry—which opened in April of 2016 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, travelling thereafter to The New York Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles—captures the breadth of that effort. What emerges from the constellation of works included in his survey is an astonishingly perfect argument, beginning with a series of self-portraits from the 1980s, carrying on through the following decade with works like De Style (1993), a study of young men at a barber shop; the similarly large scale Garden Project (1997) paintings of public housing projects; to a series of Rococo-style vignettes (2000), featuring men and women lolling on grassy knolls or beside wishing wells, surrounded by cartoonish clouds of hearts. Marshall uncovers darker histories within these works as well, such as in his portraits of the Stono Group—members of a 1739 slave rebellion who have since been marginalized in the history books—to challenge the ways in which formalism re-inscribes a system of violence through omission. Even more recent works include figure paintings about painting, where various subjects pose in the artist’s studio, or sit before easels in the midst of their own (often paint by number) backdrops. Abstraction continually plays in and out of all of these works, but appears most vehemently in a final series of pink, black, and green color fields from 2014 and 2015. These Untitled (Blot) works are reminiscent of Rorschach tests, standing in as strange mirrors in the figurative ensemble Marshall otherwise provides. Perhaps, as a dangerously self-diagnostic tool, these blots reflect patterns of thought and invisible habit embedded not only in art historical institutions and American ideology, but the viewers, critics, and conversation that attend them. Thankfully, Marshall’s ability to assert his hand so directly upon those old grooves of thinking offers a preliminary step to something new.

Through the accrued action of these paintings, Marshall populates the white walls of public, cultural space with a rich and complex tableau of black lives. As with all the figures he paints, Marshall’s message cannot be reduced to a single note or generic archetype, but rather a network of people, contexts, styles, time periods, and feelings—these works are disarming, rebellious, charming, dangerous, heartbroken, playful, loving, and full of rage. The stakes are high. Perhaps what comes across most when surveying over thirty-five years of Marshall’s efforts is his practiced ability to dispute the institution with its own institutional language. The result is as much an act of protest as a movement toward repair.

Marshall makes paintings—most darling medium of art history!—and primarily representational paintings at that. Scale is also of importance; he produces history paintings so large they cannot help but command attention.[2] As is characteristic of Marshall’s artistic abilities—his mastery—the paintings are packed with references and allegorical hints, out of which a coherent picture emerges. By quoting religious iconography, folk art, medical imagery, traditional representation, and modern abstraction in turns, Marshall demonstrates how a single flat and static picture plane is produced by an ongoing, atemporal suite of influences. In other words—and maybe even like Benjamin’s Angel of History—the past happens simultaneously in front of us, on the canvas. The only question left unanswered is what might come next.

“This is how the angel of history must look. His face is turned toward the past. Where a chain of events appears before us, he sees one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise and has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm drives him irresistibly into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. What we call progress is this storm.”[3]

It therefore seems fitting that Marshall’s referential strategies—his interest in quoting culture and history—begin with A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980). Inspired by Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and born from dissatisfaction he felt about the abstract collage work he had been making since graduate school, Marshall dove into human representation, publicly vowing never to paint a white subject. The figure in the portrait is hard to make out except by silhouette: he wears a cowboy-like hat—a gambler or fedora—which might be significant given Marshall’s specifically American interests; otherwise you see the bright gleam of a smile with one tooth missing, the whites of his eyes, and the corner of a collarless, button up shirt peering out beneath an equally dark coat. This is the artist as a shadow of what he once was—the “once was” like the receding and inaccessible shape we, viewers, know to exist but cannot see. The picture marks a point of origin, the beginning of a thought that continues to unfold and develop from this point in his work onwards. It is similar perhaps to the opening passages of James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, “Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo.”[4] Like Joyce, Marshall builds from this portrait forward, and like Joyce’s protagonist, Stephen Daedalus, the exhibition maps the development of Marshall’s artistic and intellectual vision, gaining strength and virtuosity as it goes. Not long after, in 1981, Marshall quotes himself in Portrait of the Artist & a Vacuum. The first 1980 self-portrait appears in a frame hanging on a red wall behind a vacuum cleaner that is neither plugged in nor put away. As that first self-portrait captures Marshall’s early commitment to the human figure, so this second iteration captures his interest in the figure’s context, his or her domestic spaces—for just as black bodies have been omitted from the history of art, so has the everydayness of their ranging domestic lives.

De Style (1993), an improvisational homonym to the art historical movement De Stijl, marks another turning point. Here, Marshall goes large—spreading into almost ten feet of canvas, while continuing to articulate a vernacular style of marginalized American life. Elements like the patternned floor tile, product packaging, plants, and drawer handles flatten into the picture plane, as both abstract and representational elements. “In De Style, Marshall sneaks into the picture the rectilinear compositional structure and flat planes of color that are characteristic of Mondrian: the red rectangles of the sides of the counter, the white of the counter’s drawers, the wavy quadrangle of blue that hangs in the upper left corner, and the yellow of the trashcan create a syncopated visual rhythm that gleefully recalls Mondrian’s own.”[5] Marshall captures an autonomous and cohesive world, one that acknowledges the existence of art historical movements while challenging the deep-seated and various assumptions embedded within it.

This painting was the first of Marshall’s to be purchased by a museum. Its acquisition by Los Angeles County Museum of Art marks the early success of Marshall’s campaign to destabilize institutional definitions of beauty and style, troubling their otherwise lily-white ideals. School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012) belongs to the same family of work. Using a predominantly Pan-African pallet of red, black, and green, Marshall paints twelve figures—both male and female—busy in a beauty shop. As with De Style, he takes advantage of the architectural space to insert cultural referents like Lauryn Hill’s 1998 award-winning album, TheMiseducation of Lauryn Hill hanging above the door, or the shop clock with “Nation Time” written on its face, an inscription that simultaneously quotes the live album by saxophonist and composer Joe McPhee, and the 1970s Black Power Movement. Marshall includes an exhibition poster from Chris Ofili’s 2010 exhibition at the Tate Britain, winking at the artist’s landmark inclusion in institutional space, as well as more personal items, such as the graduation picture of somebody’s daughter or sister pinned to the shop wall. Despite this fairly direct referential approach, there are curious breakdowns in the representational logic—the most obvious being an anamorphic face of a Disney-esque blonde-haired, blue-eyed girl, who occupies the foreground of the space. This is the image that interests a child in the picture plane, as he or she stoops to decipher its meaning. Like Holbein’s skull in The Ambassadors (1533), the blonde cartoon infuses the otherwise robust commitment to black beauty with a shadow of undeniable influence. Marshall’s composition ensures that both subjects inside the picture and viewers looking at it have to negotiate the character’s specter. The painting’s environment is one that is compressed and foreshortened—a feeling heightened by the mirrored surfaces lining the back wall, adding a sense of surveillance and restriction to the picture. The horizon line of the composition is very near at hand. Additionally, a male figure, captured in profile on the right hand side wears a ruffled and vaguely historical collar that points to another shadow of the past.

For Marshall, the mark of history is close at hand, whether juxtaposing windowless shot gun style houses used to house slaves with the study of a woman’s body in Beauty Examined (1993), or the awesome slippage between modernist and graffiti mark making in the Garden Project series. He includes the faces of great Civil Rights Activists in paintings like Souvenir I (1997), and conversely memorializes bystanders of a lynching in Heirlooms and Accessories (2002). Whereas the focus of the original photographs tend toward the bodies of two black young men hanging over a sea of white faces, Marshall renders the black bodies in white disappearing them into the white picture plane, and framing instead three white women who gaze directly, with disconcerting casualness, at the camera—frozen forever in their complicity. Marshall does not shy away from our violent past and its pressure on the present. In the portrait Lost Boys: AKA Lil Bit (1993), a young man stares directly at the viewer, surrounded by a line drawing of a halo—above him, a cloud of floral-like patterns and writing are combined to produce a memorializing effect. One assumes this young man is dead, or perhaps has become a criminal of some sort, a lost cause. The portrait evokes troublesome cultural associations—troublesome because in fact there is very little to suggest what this young man’s lost-ness is about, except for often invisible but collective cultural assumptions about the lives of young black men. These are the associations Marshall actively subverts. Sometimes his figures are dangerous. In The Portrait of Nat Turner with the Head of his Master (2011), Marshall depicts the figure right after committing an act of violence: a man in simple brown clothes carries a blood soaked cleaver. A decapitated head lies in the bed behind him. Identified by name, Turner returns the gaze at the viewer without apology. Unlike the women in Heirlooms and Souvenirs, however, Turner is not casual. Marshall further complicates the viewer’s relationship to violence in The Actor Hezekiah Washington as Julian Carlton, Taliesin Murderer of Frank Lloyd Wright Family (2009), in which one actor poses as another historically identified criminal: the servant who murdered Lloyd Wright’s mistress’ family around the same time the architect had abandoned his own.

In all this work, it is as if Marshall gives voice to the ways in which young African American men are easily identified as threats due to a historically erroneous conflation. The entirely dangerous weight of hierarchy, confusion, role-playing, and exploitation boils up. A young woman seated on a carpeted floor at the top of the stairs has a yearbook at her side, exclaiming in cartoon clouds, SOB SOB (2003). Through painting, Marshall shoulders—or has to shoulder—the horror of our collective past with unwavering attention, playing with what is and is not visible, and its implicit relationship to violence and social patterns. As with Scipio Moorhead, Portrait of Himself, 1776 (2007), or the Untitled painters from 2008-2009, an inherent circumstantial violence marginalizes those artist’s potential. Black Painting (2003–2006), a work that took three years to complete, depicts Black Panther member Fred Hamptom lying in bed just before a police raid that killed him. Here, Marshall explores blackness as an essential and normative condition to such an extent that the painting itself is almost impossible to photograph. It is is inherently resistant, denying a certain reproducibility in favor of a concentrated discernment. Viewers have to spend time with this work, projecting themselves into that room where we know, at any minute, the police will arrive and disrupt the darkness forever. Black Painting’sranging and intrinsic quality of blackness becomes a normative condition of the work.[6] By challenging the otherwise predominantly white western norms of most museum collections, it gives rise to Marshall’s other seemingly impossible, though perhaps more mundane, challenge: to maintain a steady look at colonial history, to keep a hand on an American present, and all the while maintain a positive outlook for the future.

Marshall identifies this as a common aspect of black experience. “You have people trying to reclaim that past, but also trying to survive a difficult present and project themselves into a future with more possibility.”[7] Indeed, as Marshall suggests, what would help the entire country move through our racial divide is to take a collective responsibility for our troublesome roots: that the American dream has not been available unequivocally to all—that too many have benefitted (and continue to benefit) from its exclusionary tactics—but that we might yet make it so. As Claudia Rankine recently wrote in the New York Times Magazine, “The legacy of black bodies as property and subsequently three-fifths human continues to pollute the white imagination. To inhabit our citizenry fully, we have to not only understand this, but also grasp it.”[8]

This is his first retrospective. As its title suggests, and according to the challenge of Marshall’s mission, Mastry is a historical achievement. The weight of that accomplishment is staggering. It is as though he set himself upon a seemingly impossible mission that answers to the entirety of art history, imposing himself upon that history with a propositional, and complex revision.

Like a dogged activist, he insistently asserts not The Black Body, as a singular entity, but many black individuals into historically white institutional spaces—not in just one museum either, but three: the MCA Chicago, The Met, and the MOCA in Los Angeles. As co-curator Helen Molesworth writes, “Marshall’s oeuvre is a sustained exegesis on the ways in which the museum, painting, and the discipline of art history have participated—both historically and presently—in the defining, and maintaining of race as a naturalized category.”[9]

Two final notes come to mind. First, a quote, not by a curator or art historian, but by writer, journalist, and correspondent for The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates:

“That was a moment, a joyous moment, beyond the Dream—a moment imbued by a power more gorgeous than any voting rights bill. This power, this black power, originates in a view of the American galaxy taken from a dark and essential plant. Black power is the dungeon-side view of Monticello—which is to say, the view taken in struggle. And black power births a kind of understanding that illuminates all the galaxies in their truest colors. Even the Dreamers—lost in their great reverie—feel it, for it is Billie they reach for in sadness, and Mobb Deep is what they holler in boldness, and Isley they hum in love, and Dre they yell in revelry, and Aretha is the last sound they hear before dying. We have made something down here. We have taken the one-drop rules of Dreamers and flipped them. They made us into a race. We made ourselves into a people.”[10]

Second, an improvisational music performance by Wadada Leo Smith and the Golden Quartet at The Logan Center at the University of Chicago last October. In conjunction with Smith’s exhibition of scores at The Renaissance Society, the group played a song later referred to as “Freedom River Something” — a song with more than one name, Smith said, calling it also “Mississippi Runs Deep, Dark, and Flows.” It is not just about the idea of history, but rather about objects that fell into the river and later emerged as undeniable artifacts. It is about a river that runs through the entire country. “It’s about a tale of liberty and human rights, and when we play it, it is a struggle.” It was a struggle. The musicians hadn’t planned to play the song before they arrived; it wasn’t rehearsed and the performance was stressful to watch—Smith acting as conductor regularly exhibited frustration. A microphone positioned inside the grand piano slipped onto the piano strings over and over again so that the pianist, Anthony Davis, regularly interrupted his playing to rise and resituate the mic. And the musicians got lost a few times as well, though one could only tell by the fervent way one or another of them paged distractedly through the score. To hear it, though—trumpet, piano, upright base, and drums working through a live conversation—was “to overcome a moment,” as Smith said, addressing the room afterwards. He described the importance of that effort and difficulty, stressing the fact that such collaborations are only possible with trust. “Every part [of the song] that doesn’t work, gives us much more confidence that the next part is going to work out. And if the next part doesn’t work, it builds our confidence to the maximum, that the next part is going to work. And if none of them work, that’s what beauty is…and that’s where art comes from…It [art] is about the human experience to overcome and achieve. It is like those memorial objects that were submerged into the Mississippi. They didn’t stay down there. They came up and forced people to look at them and say, ‘This is what happened.’”[11]