Egypt in the Eyes of Jean Pascal Sébah at 5. Gallery

The following article was published by Southwest Contemporary in June 2021.

Egypt

May 28–June 18, 2021

5. Gallery, Santa Fe

Egypt, a curious and somewhat stupefying show currently on view at Santa Fe’s 5. Gallery, offers a display of archival albumen prints from 1875-1876 depicting Egyptian landscapes and portraits. Though it’s a modest exhibition volume-wise—just nineteen artworks—the show acts as a doorway into the complex intersections of modern thought, its desire to objectively collect history, and the global beginnings of a mobile middle class that sent photographic postcards home by mail.

The photographs capture a number of monumental sites mid-excavation including the Grand Pyramid of Giza, Great Sphinx of Giza, and the Temple of Hathor, which appears to rise from the earth for the first time, dirt piled on its roof. The scale of these ancient monuments, often juxtaposed by tiny human-sized figures, horses, or donkeys, seem to capture history, as it’s unearthed, in its most maximum human form. Of note—perhaps to emphasize the framed production of these photographs—is the cloudless sky, a matching flat midtone in every single landscape photo.

What’s additionally curious is the way these images are by now so prolific as to imbue the photographs with nostalgia for that initial moment of discovery—a discovery on the cusp of modernity, one that coincides with the advent of photography, archaeology, tourism, and the discoverability of objective scientific truths.

The show’s six portraits—which includes Porteur d’eau (Water Porter), Egyptian Woman, two untitled photographs of men, and Fellah et son enfant (Fellah and her child)—isolate human subjects in varied, non-western attire with generic backdrops that were likely staged in a studio. With the exception of the water porter and the child in Fellah et son enfant, none of the subjects return the camera’s gaze.

This seems politically significant because of the portraits, only Porteur d’eau is attributed to Jean Pascal Sébah, a well-established Syriac-Armenian photographer born in Constantinople who worked in Egypt. Like the European commercial photographers of his time, Sébah helped disseminate a pre-modern vision of Middle Eastern residents to Western tourists.

Nevertheless, he employed a more documentarian approach, one that often situates figures in contextualizing environments—such as restaurants or busy streets—among fellow residents, granting subjects the option to return the gaze of the West by looking at the camera.

Aside from three anonymous photos, including the two untitled portraits, and Egyptian Woman, which is attributed to the Italian photographer Carlos Naya, the exhibition’s remaining sixteen prints were taken by Jean Pascal Sébah.

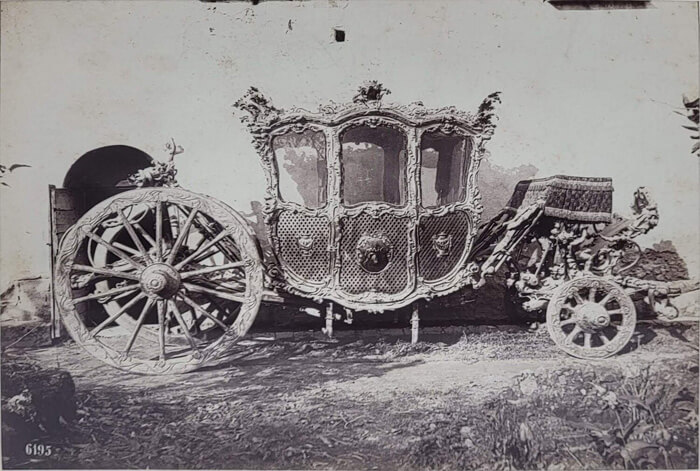

Much has been written about the ways in which the West fetishized foreign landscapes, establishing an Orientalist aesthetic that fulfilled and reinforced colonial authority under the auspices of idealizing a more primitive vision of human life. Perhaps for that reason, a photo of an ornate carriage stands out.

The carriage appears abandoned—attached to neither a person nor an animal—on a nondescript landscape run over by weeds, as though in an alley behind some house. The only indicator that the carriage may be situated in Egypt, aside from its context in the show, is a barely visible archway in the image’s left-hand side.

The photo’s provenance appears to be uncertain. It’s not attributed to an author or pegged to a year. The title is further ambiguous: Unknown (Napoleon’s Carriage?). It’s as though the camera—or whoever found the photograph—is projecting its own assumptions, fantasies, and expectations on the abandoned objects once used by the Western Empire.

Still, it’s an interesting possibility given that Napoleon’s armies were the first to mine and export Egyptian artifacts to France during the Battle of the Pyramids. They must have left any number of items behind.

Napoleon would establish the first museums to house the spoils of conquest, which became an origin point for art viewing today. His efforts would also be later used to advocate the supposedly objective first camera, the daguerreotype, which allowed one person to “copy the millions of hieroglyphs” without much trouble.

The photographs in Egypt thus capture an intersection of historic, political, and aesthetic forces through the camera of the second-generation photographer Jean Pascal Sébah, meeting the demands of tourists who sought, and still seek, the evidence of human accomplishment.