Sorry for Being a Genius: Aida Makoto at the Mori Art Museum

This article was originally published by Artslant on Feb 28, 2013.

“There is no more chastity in the Young-Girl than there is debauchery. The Young-Girl simply lives as a stranger to her desires, whose coherence is governed by her market-driven superego.” —Tiqqun,Preliminary Materials for a Theory of a Young-Girl, 2012

Aida Makoto’s retrospective exhibit, “Monument for Nothing,” is a stunning body of work, taking full advantage of its towering exhibition site. The Mori Art Museum sits on the 53rd and 54th floors of Roppongi Hills Mori Tower—a massive skyscraper built in 2003. It is the fifth tallest building in Tokyo. As part of one’s ticket price, visitors have access to a sky deck where the whole city extends beneath your feet. On clear days Mt. Fuji juts up from the horizon, as iconic in person as it is in any woodblock print. It’s a museum in the clouds. What better site for one of Japan’s most controversial and celebrated contemporary artists?

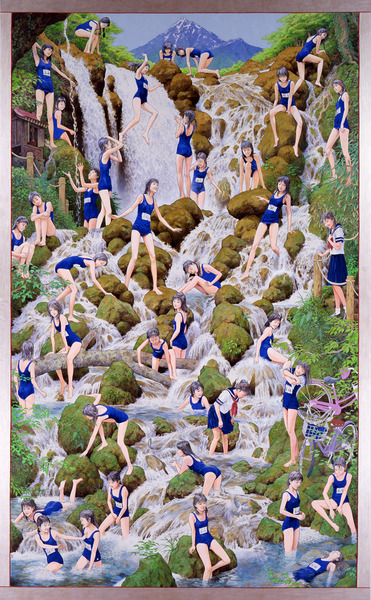

Aida Makoto is intent on unearthing latent cultural mores, as someone both implicated in and critical of society’s shadow. While this process is not entirely focused on infantilized women, Aida’s young girls easily eclipse the rest of his work—they burn a persistent impression like an afterimage, emphasizing his unique interest in blending a high-art past with a low-brow manga perversity. AZEMICHI (Path Between Rice Fields) (1991) makes a visual pun of a young girl’s part between pigtails, connecting the back of her hairline seamlessly to a path between rice fields. This work quotes Kaii Higashiyama’s (1908-1999) similarly iconic work Road from 1950—a deceptively simple landscape painting that shows the same unpaved path between green fields. Whereas Higashiyama is famous for creating landscapes that reflect an inner state of mind, Aida’s state of mind is indivisible from the young girl. With a tenderness that verges on pedophilia, the front piece of Aida’s exhibit,Picture of a Waterfall (2007-2010), depicts a vast array of young girls in almost exactly the same track and field uniforms clambering and splashing through a cultivated landscape. There is no difference between the treatment of these girls and the ones in violent compromise.

The young girls in Aida’s work are impersonal, and non-specific (even if they have unique physical characteristics). One young girl is as good as any other. Setting aside my tendency as a woman to identify with Aida’s girls, it might be useful to suspend any anatomical correlation and focus instead on the fact that Aida is not presenting real girls, but stylized representations of them. What is especially disconcerting about these representations is that there is something familiar about them. They emerge from a pervasive, cultural subconscious as a kind of archetype. The French collective Tiqqun recognizes this archetype as well and in 1999 coined their own version, the “Young-Girl”—a non-gendered umbrella term. Tiqqun suggests that there are many Young-Girls among us. We might all be Young-Girls, figures that emerge from the spectacle of capitalist society.

Blender (2001), an eight-foot tall painting showing thousands of girls in a giant, expertly rendered blender hangs at the heart of this show. It is impossible to drift past. It is a horrific meditation on violence. These tiny bodies, the sheer number of which blot out any potential for unique individuality, are all naked, all twisting, many smiling, each rendered with such obsessive detail as to feel almost tender. Pinkish water collects at the bottom of the vessel near the blade. Presumably, some invisible giant will consume them. Ash Colored Mountains (2009-11) hangs in the same room, a painting with delicately rendered piles upon piles of salary men, all in suits without eyes—similarly pristine in their illustration, they clutch computer parts. However, they have been cast aside as disposable parts—not even worth eating. The colors are flat and dull, as though all their nutrients have been drained. If these two works describe a gender binary, neither is appealing. It is unfortunate that Aida doesn’t portray the dismal state of more male subjects, as it might further emphasize the bleak reality society imposes on all its constituents. Instead the emphasis lies on the distressing (though not distressed) feminine, what continues to appear like Aida’s familiar—a spiritual or archetypal presence he cannot separate from. The erotic potential of her body and its affliction is the red herring.

Blender and Ash Colored Mountains both offer the same societal portrait from different angles. The Young-Girl suffers the least, even when subject to violence, because she is so impossibly remote (and therefore unpossessable, despite her leering charm). Like the salary men, she is a condition of capitalist society. The Young-Girl is vacuous and torture-able. She has no interiority because she is an image—pure surface. She is the face of capital. “The Young-Girl only excites the desire to vanquish her, to take advantage of her.”[i] She is as familiar as any pornographic actor, impossible to reach through the screen she appears upon. She “occupies the central node of the present system of desire,”[ii] and this is what Aida is exploiting, seeming at once excited and anguished by his participation in this system. He is able to draw that perversity out from the margins—particularly referencing Otaku fan-boy culture—bringing its impulses to the fore of society’s consciousness by installing them in a museum. At the heart of his practice, Aida wrestles a distinctly Japanese form of misogyny; a wildly popular though subterranean lust for female naïveté and the exploitation thereof—a tendency that seems to be built on feelings of inadequacy, as the monetary contributions of women undermine the trope of the Salary Man. Aida delves fearlessly into these tropes, exorcising the ghosts of a sadist in public.

A last room of the exhibit is set aside for those 18 and up. There is a warning against its contents and soft curtains drop from the doorframe. Inside, everything is pleasantly dark, allowing visitors a sense of discretion. We are given permission to dwell on these works, whereas the stark and unflinching Blender took place in broad view. In the back of the Adult Room, we see a giant painting of a woman getting raped by a dragon. A placard on the wall explains that this single piece established Aida’s career. The Giant Member Fuji versus King Gidora(1993) harkens back to The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife—a famous image of Japanese erotica from an 1814 woodblock print. In that earlier predecessor the woman expresses her pleasure. In Aida’s version, we see a woman with a tear falling from her remote face—this is the only woman crying in the whole exhibit and she does so in the dark. She is on the verge of death, or perhaps just dead. Intimacy with her image as a poignant victim seems almost possible. To the left of that painting Aida masturbates to the kanji for “beautiful young girl” painted on a wall in a sixty-two-minute video. An adjacent placard explains that he was so uncomfortable during the filming, it took him an hour to ejaculate. In the dark, again, we are given a sense of access that the rest of the exhibit denies. The artist would seem awkward in this room, except of course that it’s staged. Like a pornographic film, we can’t trust the narratives provided. Some of the most troubling paintings are hung here—paintings of women with their legs and arms amputated and bandaged—to make them more like dogs. They smile with studded collars. Another series of cruder cartoon-like drawings depict women as food—entirely consumable. Perhaps in an equally direct transferral, photographs show naked women with Aida’s paintings directly on their bodies, rendering the personal, biological material into an impersonal and abstract capital value. Here, we are indulged with a sense of trespass, at once distant and privileged. One feels underground, secure and yet alienated. It is easy to forget how high above the city we are.

People ask if Aida is misogynist all the time. There has been a good deal of healthy outrage around the content of his work for obvious reasons. It is worth noting, however, his delight in provocation, a tendency that is also ubiquitous in all of his works. Yet he maintains an ironic distance throughout (even renaming this show “Sorry for Being a Genius”). Still, there are Aida’s collectors to think about—who buys these works and where are they hanging? I imagine them in high-rise apartments owned by very wealthy men with dubious appetites. It stops being so ironic at that point, as the artist’s distance from the purveyor of desire disappears. Like his viewers in the dark Adult Room, like the Young-Girls he paints, like all of us, Aida is both complicit and exploited.

(Image on top: Aida Makoto, Blender , 2001, Acrylic on canvas, 290 x 210.5 cm.; © Mizuma Art Gallery / TAKAHASHI collection, Tokyo.)