LIFE IN THE ANTHROPOCENE: ENVIRONMENTAL EXHIBITIONS FOR THE HUMAN EPOCH

The following article was originally published by Artslant on January 6, 2015.

I go back and forth between feeling like Anthropocene is a buzzword for contemporary hysteria—our generation’s equivalent to the Cold War—and recognizing it as a practical reality. Either way it is the nexus point between published facts and our dogged consumerist lifestyles: we live in the 6th Great Extinction, yet guzzle gas and consume plastic with aplomb. Responding to an already lush rubric of 2013 exhibitions, several 2014 shows explored ecocritical themes, as will a number of presentations in the coming year, all composing vivid curatorial landscapes that challenge our historical approach to the material world.

Philippe Parreno, Anywhere, Anywhere, Out Of The World, Exhibition view at Palais de Tokyo, 2013. Photo: Aurélien Mole

Perhaps that’s why Philippe Parreno’s 2013 exhibition left such an impression when I caught the tail end of it in January 2014. Parreno gutted the Palais de Tokyo, creating a surreal, interactive environment that conveyed an end-times-feeling. A few months later Angelika Markul installed her three-part exhibition, Terre de départ (Land of Departure) in the same museum’s ground floor space, where she set a white stage for a large video screen. The platform extended to support a set of white debris: pipes that looked like they may once have been used in a playground swing set. On screen she projected footage from Chernobyl where the camera pans around, capturing a too-still forest punctuated occasionally by abandoned buildings. Everything feels frozen in time—a feeling I remembered when reading that trees in Chernobyl don’t decompose; latent radiation prevent fungi, microbes, and certain insects that would otherwise turn fallen trunks into dirt. An adjacent room in Markul’s exhibit opened up on the artist’s two-channel projection of twin backwards flowing waterfalls. They flickered cast light over Markul’s surrounding installation—hard to see in the dark, reading nevertheless like a pile of dead and inert bodies washed up in an oil slick. In her final video a 2001-like telescope shifts with robotic grace, presumably to see the sky beyond the human eye.

On Landscape Projects, On Landscape, Installation view at Guest Projects, London, 2014. Photo courtesy of artists

In London a group of artists installed their self-titled exhibition On Landscape, featuring a library of artist books dedicated to landscape representation. I found the artist collective on twitter, following a feed of photos that capture interactions between natural (nonhuman) and unnatural (human) elements. On Landscape’s examples corrode the traditional delineation between nature and culture, favoring the blurred and reciprocal conversation that emerges between skyscrapers and plants instead. The landscape is a hybrid, like the newly discovered rock, “plastiglomerate,”—composed of plastic particles washed up on the beach, sand, and volcanic rock, the material gloms together from beach campfires, and signifies plastic’s new geological presence. Perhaps it’s better to explore the potential in these blending, collapsing borders than mourn the dissolve of a bygone ideology dedicated to some pure Alpine vista.

Greg Stimac, Santa Fe to Billings, 2009, Archival pigment print, from Phantoms in the Dirt. © Collection of Museum of Contemporary Photography, 2009.347

Nicolas Bourriaud curated the 2014 Taipei Biennial; he called it The Great Acceleration, citing that more robots use the internet on a daily basis than human beings. During an interview he asks, “If we takes the anthropocene as a hypothesis, how does it transform our vision of the world? Is there still such a thing as a direct interhuman relation?” Fifty-two artists and collectives appeared. And let’s not forget Phantoms in the Dirt, an ambitious group exhibition curated by Karsten Lund at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago. Or the group show in Paris curated by Anne Bonnin, Humainonhumain, who claims it is the body, first, “that is…affected by nonhuman reality.” In Berlin, Haus der Kulturen der Welt organized the first meeting of their multidisciplinary Anthropocene Working Group to suss out the consequence of our time, and was covered by the USNews. I didn’t go but was given the publication afterwards—a heavy bound booklet.

Adam Avikainen, CSI Department of Natural Resources, 2014, from HKW’s Anthropocene Working Group. Courtesy and copyright the artist

There is so much to read. In The Aura of a Hole, A. Laurie Palmer’s decade-long research project about material and how it moves in and out of networks (personal/economic/ecological). It sits on my shelf beside Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine—both books that reinforce the intersection of ecology and capitalism. They remind me again of Parreno. What will the future hold?

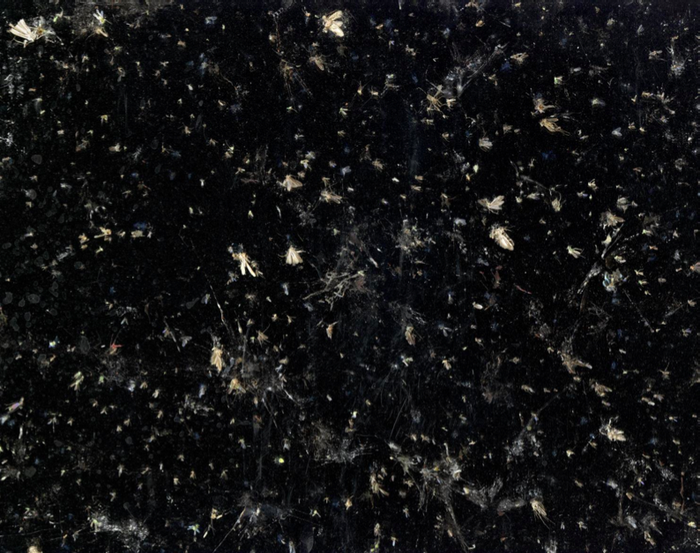

In San Francisco, Robert Zhao Renhui (author of a 2013 Guide to Flora and Fauna of the World featuring man-made/modified plants and animals) installed his homage to easily dismissed insect encounters in Flies Prefer Yellow. Nearby, Landscape: the virtual, the actual, the possible? at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, an exhibition that connects Californian utopic ideologies with Silicon Valley and the Pearl River Delta region in China, where most of the world’s electronic products are produced, in order to reflect on the intersection between nature and technology. Green Peace jumped in also, erroneously installing their logo beside the ancient Nazca Lines in Peru, (itself an early sign of human’s ability to leave a footprint). Despite all that, my daily routine seems the same, suggesting some surreal dream state in which all signs suggest a change in consumer patterns are in order, without the embodied action to do so; as uncanny as robots racing camels in lieu of human jockeys.

Marcus Gruber, The Art of Hunting Mammoths: Altamira Cave, Anthropocene Milestones No. 1

Father – “Son, what’s taking you so long! The mammoths won’t wait for us!”

Son – “I think I would rather be an artist.”

Future curatorial endeavors continue to chew on the subject. Claiming to be “the first major exhibition in the world to look at an issue that will be decisive for the future,” Welcome to the Anthropocene opened at the Deutsches Museum this past December and will occupy over 4,500 square feet of museum until January 2016. Included in DM’s exhibition programming is a series of 30 Anthropocene-comics (pictured above) and a virtual online corollary to the show. In the Netherlands, BAK announced a “research exhibition and discursive environment,” called the Anthropocene Observatory that aims to deconstruct the intersection between geological and political history. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, Witte de With hosts its own three-part exhibition, beginning with Art In the Age of…Energy and Raw Material, a group show asking how art and geothermal activities influence one another. It also has an ongoing tumblr with (among other things) old oil advertisements. Back in the States, Milwaukee’s INOVA plans Placing the Golden Spike: Landscapes of the Anthropocene opening this March and running through June.

Emergent conclusions provoked by these exhibits will hopefully put an end to the middling shadow box of ecological propaganda, shifting instead to more proactive changes in societal habits. Nature, as a pure, nonhuman ideology may not exist, but the world in which humanity is embedded remains profound, strange, and reciprocally complex.

(Image at top: Marina Zurkow, Still from Mesocosm (Wink, Texas), 2012, to be included in INOVA’s Placing the Golden Spike: Landscapes of the Anthropocene, 2015)