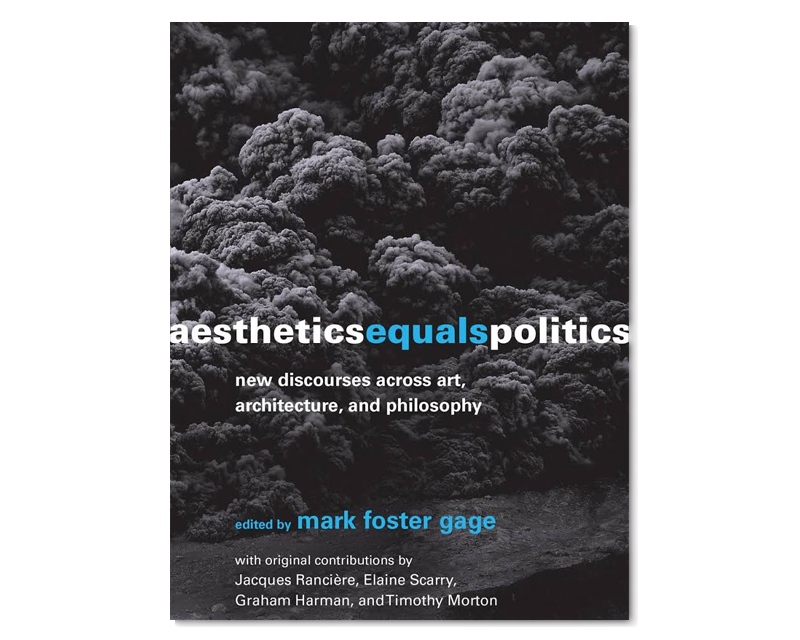

Aesthetics Equals Politics

Edited by Mark Foster Gage with writing by Mark Foster Gage, Jacques Rancière, Elaine Scarry, Graham Harman, Timothy Morton, Ferda Kolatan, Adam Fure, Michael Young, Nettrice R. Gaskins, Roger Rothman, Diann Bauer, Matt Shaw, Albena Yaneva, Brett Mommersteeg, Lydia Kallipoliti, Ariane Lourie Harrison, Rhett Russo, Peggy Deamer, and me. The book includes my essay about cats belonging to myself, Leopold Bloom, Broodthaers, Art orienté object, and the Walker’s annual cat festival. Pick up a copy here. Or you can read part of the essay below:

The Strangers Among Us

What happens when we think about our most everyday companions and the ways they disrupt or accommodate our human structures? For instance, I tend to forget how strange our cat is. It is easy to take her presence for granted. After ten years of cohabitation, I am accustomed to both the cat’s form and personality. I have a lexicon of adjectives used to describe her: cute, reserved, sweet, independent, inquisitive, bossy, self-possessed, calculating, scampy — the latter inspired by her special proclivity to seek out abandoned, half-filled water glasses in our house and — while staring at me from across the room — insert a paw into the lip of the glass so as to knock the whole mess over. The activity provides our cat evident delight despite (or maybe because of) whatever rage it elicits in me.

Our understanding of one another has developed patterns over the years, patterns that lead me to say I know her, our cat. Little Grey. I can describe her easily: she has yellow green eyes and a mottled gray coat that burns ever so slightly pink around the edges when backlit. Compared to other cats I’ve encountered, she is small, but like other cats quite athletic, prone to naps, vocal, and appreciative of dietary schedules. I would call her courageous without any evidence to prove as much. I would also say she is nice, citing her apparent restraint as proof: she rarely if ever bites or scratches humans and instead of killing insects follows them around until distracted by something else. Like all of the adjectives in my wheelhouse however, niceness brings with it so many anthropocentric associations as to be misleading. In fact, all of those words fail, applying a human criterion that essentially eschews the host of unpredictable, irregular, and barely noticeable aspects of her character. Like easily overlooked letters in English words — silent g’s, h’s, or r’s unearthed only by strange accent — she has certain traits and tendencies on the very edge of my perception, possessing even more that elude me entirely. Whether I am not literate enough in the gestural vocabulary of her ears, or because I cannot parse every consonant in a mew, my adjectives fail to translate all of her; her personality is driven by its unique manifestation of nonhuman cat-ness. She lives only partially in language, orbiting the periphery of human speech like a foreigner who’s taken up residence abroad. While impossibly inadequate, my words nevertheless give me access to her friendship and their regular use reflects, in part at least, the habit with which we relate to one another. I can anticipate her; she anticipates me. Despite our differences, we are friends.

The Walker Art Center has an annual Internet Cat Festival in Minneapolis that attracts as many as 10,000 visitors — people who arrange themselves in stadium seats to watch preselected cat videos and vote on their favorites. No doubt the museum is grateful for the event — not only because it captures a contemporary phenomenon, but also for its administrative statistics. (Imagine the delight of their grant writer when asked to report on museum attendance.) I too enjoy the celebrity of the species. Like his 48,000 followers, I could watch Maru dive into a different box all day.[1] Part of the appeal of these clips reflects exactly the strangeness I’m reaching to articulate: a specific form of — often performative — cat eccentricity. It resists total assimilation to human society, while being relatable enough to be celebrated. Take the Ninja Cat as another example — the leggy animal appears on the far end of a corridor, and only approaches the viewer off-camera. Each time the camera returns to its subject, the cat is closer, larger, and ever so slightly menacing. Or Teddy The Asshole Cat who sits calmly on a dresser until deciding, without provocation, to knock over a nearby bottle of pills; he looks at the camera yawningly thereafter. The strangeness of a feline companion is easily taken for granted in the midst of domestic routines, but every so often something happens to illustrate the interspecies gulf between us.

When we first meet Ulysses’ protagonist, Leopold Bloom, he stands in the kitchen talking to his housecat. The animal does not repeat a single phrase; its diction changes according — it would seem — to Bloom’s various prompts. Although Joyce uses the same format to relate other human conversations in the book, the animal’s meaning remains inaccessible; it is similarly impossible to gauge how much of Bloom’s meaning is conveyed to the cat. Still, they answer one another in a style of amicable habit, like neighbors speaking different languages, familiar with the impasse of mutual understanding while nevertheless capable of enjoying a predictable companionship.

The cat walked stiffly round a leg of the table with tail on high.

—Mkgnao!

—O, there you are, Mr Bloom said, turning from the fire. The cat mewed in answer and stalked again stiffly round a leg of the table, mewing. Just how she stalks over my writing table. Prr. Scratch my head. Prr.

Mr Bloom watched curiously, kindly, the lithe black form.[…]

—Milk for the pussens, he said.

—Mrkgnao! the cat cried.[2]

The cat’s phrases would seem identical at first, except for an easily overlooked r — as significant a difference as an element of code in DNA. In that tiny differentiation, the cat indicates the subtle, though possibly infinite variation of replies at her disposal. To take the presence of such a small letter seriously not only grants the cat a deliberate capacity to answer Bloom, but also highlights the human propensity to dismiss such differences as arbitrary.

Every so often I glimpse the opaque white flesh surrounding our cat’s colored iris and I am struck by the reptilian character of her eyes. It occurs to me that if she was even twice my size she would not only kill me, but enjoy doing so. Suddenly I touch upon the uncharted landscape of her being — that reticent horizon that evades apprehension as a monstrous, chimerical figure emerging in a dream, and — defying translation — is shrugged off and forgotten the instant I wake up. It has no purchase in the linguistic chart of terms I use to filter my experience; as such it dissolves the minute I encounter the hemmed edges of quantifiable things: the bed, the pillow, the floor, the sink. How indeed am I to incorporate and map her unknown and particular beastly-ness in an anthropocentric vocabulary? Or better yet, how do I remember the vagaries of her impression if I cannot hobble its corners with words? If I happen to catch Little Grey studying the shower, (a recent habit she developed during which she appears lost in thought for hours at a time while staring at the drain), I puzzle over her remote though evident purpose. Or, when interrupting one of her naps, I touch the bottom of a paw and, petting the soft, strangely distinct pads there, feel her wrap that same paw ever so slightly around my fingers like a baby grasping the hand of a doctor. These fleeting moments highlight my own inability to comprehend the subject of her mind. She is not a snake, nor a child, nor is she my predator. She is a cat, something unsettled and unsettling. After she has seemingly spilled water everywhere on purpose and thundered off in a great, seemingly triumphant gallop across the room, I realize perhaps this cat has a sense of humor, in which knocking over glasses is a gag. Could it be? But the question itself belies our estrangement, for — if I know her, if we are friends — I should know the answer before ever having asked. Measuring humor is one of the first things you notice about a person. Yet here, I am groping in the dark like one who suspects an intimate friend of stealing. Does my suspicion illustrate some instinctual insight into that friend’s most private thief-soul? Or do I only prove my own blindness, overlooking that companion’s integrity and in so doing, destroy any viable trust between us? Beneath our familiar patterns, I am alienated from this dear being.

In The Animal that Therefore I Am, Jacques Derrida shares a series of reflections that pass from Alice In Wonderland to Genesis to Plato’s Republic under the overseeing and slightly uncomfortable gaze of his own cat.

No, no, my cat, the cat that looks at me in my bedroom or bathroom, this cat …does not appear here to represent, like an ambassador, the immense symbolic responsibility with which our culture has always charged the feline race, from La Fontaine to Tieck (author of “Puss in Boots”), from Baudelaire to Rilke, Buber and many others. If I say “it is a real cat” that sees me naked, this is in order to mark its unsubstitutable singularity. When it responds in its name (whatever “respond” means, and that will be our question), it doesn’t do so as the exemplar of a species called “cat,” even less so of an “animal,” genus, or kingdom.[3]

Although whatever idiosyncratic character his cat possesses remains hauntingly in the background of his text, she is nevertheless a singular presence and to highlight her gaze, Derrida regularly reminds readers of his own nudity. He is naked and, with Biblical theatricality, becomes self-conscious under her implacable scrutiny. Within the cross-section of this structure — the cat, his nudity, and the presentation of language — he reflects upon humanity’s historic relationship to its animal companions, adding the prescient remark that, “…no one can deny today this event — that is, the unprecedented proportions of this subjection of the animal.”[4]

Of utmost importance for him is to establish whether or not the animal can respond. If humor is an acceptable form of response, does the animal have a sense of humor? Can it understand me? Notice Little Grey, a gendered, she-cat, suddenly becomes unspecific in the turmoil of these questions, dissolving into a more general pool: the thingness of an animal (itself a dubious category). Of additional interest is the human privilege endemic to my question: can “The Animal”—an umbrella intended to contain an immense and various multiplicity—reply to me on my own singular terms, in my language? If we suspend that privilege, confusion results.

The said question of the said animal in its entirety comes down to knowing not whether the animal speaks but whether one can know what respond means. And how to distinguish a response from a reaction.[5]

At one time, I lived in an apartment gallery with this same cat where we hosted art exhibitions on a regular basis in our living room. An exhibiting artist and curator published a call to take other people’s object collections on loan for the duration of an art show.[6] Hundreds of expired Starbucks gift cards, Pez dispensers, protest buttons, wine bottle bags, beer bottle tops, old champagne corks, rubber ducks, used band aids (!), journals — sentimental multiples in ranging sizes and conditions were subsequently arranged on one side of the apartment, occupying 300 square feet with a brightly-colored tableau that at once approximated outsider art in its aesthetic, while reminding the viewer of humanity’s singular capacity to acquire disposable goods. It was a cat’s playground. Although Little Grey did occasionally do a running jump into the piecemeal landscape for my benefit, she consistently preferred to harass a volunteer who watched the gallery on the weekend. During his six-hour tenure, Little Grey would leap into the installation about two or three times — particularly when visitors were present — sending all manner of objects flying; it would take another twenty minutes for Young Joon to put everything back in its proper place, always under the adjacent (and dare I say smug) scrutiny of his feline adversary. Within the medium of that material installation, Little Grey reacted to the two of us differently.

The animal’s ability to respond answers a historical lineage of philosophical questioning intended to articulate the border between human and nonhuman spheres. Responding is significant because it implies an interior judgment that would reflect a complex active, and self-possessed relationship to the world. Derrida draws on biblical history in his essay, pointing out that Adam and Eve’s defining moment arrives with the animal, or serpent. The philosopher’s nudity similarly illustrates his capacity for shame, a capacity that would seem to differentiate him, as a human, from the cat, as an animal. Within the biblical paradigm, animals are always dressed in fur, neither shameless nor shameful.

Except for the snake, biblical animals rarely answer.[7] Birds sing as symbols of God’s will and the animal brought to sacrifice gives its life symbolically to provide humankind access to God’s favor. Sacrificial killing reinforces a theoretical border between human and nonhuman spheres; while God forbids killing absolutely, he takes exception with animals. “One could say, much too hastily, that giving a name would also mean sacrificing the living to God,”[8] Derrida says, as though to suggest an effect of Adam’s nouns is to generalize a group who’s killing is sanctioned, a group unable to reply in the prescribed language of men.

Little Grey resists restrictions I impose upon her territory; her power to disrupt those bounds is a game of sorts. An intervention. How odd, she must have thought, that these humans so painstakingly replace the objects they have accumulated in such bizarre and pristine order around the gallery apartment. Or watching me dress in the morning, she might play the anthropologist and puzzle over the strange effort with which I actively and ritualistically reinscribe the division between my body and its environment — dressing, undressing, and redressing with sequences of obligatory fabrics in different formations; so, she might think, this person evidently struggles under the effort of her conviction, differentiating her “I” from the other that is everything else.

My friend’s grandmother had a pet phrase: You say it so often, it must be true. Could this be the real source of Derrida’s shame? Not the original sin of Adam and Eve per se, but rather some derivative: his own elaborate preoccupation with categories, precepts, and hierarchies used to identify, enclose, and evaluate the self. A process by which conclusions are drawn that thereafter inspire subsequent exceptions and anomalies, as though in this exercise he (we) illustrate/s the delicate and shifting foundation of human identity. This is inside, not outside. This is art and this is not. This is my essay about a cat.

Marcel Broodthaers recorded an Interview with a Cat in 1970.[9] The conversations lasts four minutes and forty-two seconds. In the first few minutes, the artist peppers the cat with questions about art in French. He begins by asking if the cat thinks a painting —neither seen nor described — is a good example of conceptual art. The cat offers a small miew in answer.

“Yet doesn’t this color call back to the kind of painting that was being done in the period of abstract art?” Broodthaers asks. And the animal answers with a series of similar but nevertheless distinct phrases, indicating what Broodthaers apparently suspected at the outset of the interview, namely that the cat will respond, and to such an extent as to appear opinionated. The two carry on together from there: Broodthaers raises the specter of academicism, followed by questions about the art market — remarks the cat takes in evident stride as it responds with its own assortment of strange, unintelligible answers. The first part of the conversation concludes with Broodthaers’ suggestion that museums ought to be closed. To that, the cat does not answer.

On the surface, the cat in Broodthaers’ interview is incorporated into a history of surrealist games. The animal becomes a foil for the art critic, the clown parodying conversations around the art world and its affiliated market. Cast in this role, the animal has nothing reasonable to add to that aesthetic discourse. Instead it mocks sophistic humans who presume their own lofty views, perhaps reflecting the artist’s contempt for art critical discourse on the one hand, while setting “Art” aside, as something unquantifiable.

Despite that interpretation, Broodthaers and the cat share a call-and-response dialogue; throughout the recording the cat remains enigmatic and embodied at once, persistent in the use of its self-directed voice. The second part of the interview features the artist alternating between two mutually exclusive statements: “Ceci un pipe” and “Ceci n’est pas un pipe.” Between those phrases spoken in French and English, the cat replies in similar though increasingly emphatic phrases. The cat’s voice — so strange and singular — can only emphasize its source: an individual with agency and finite duration; one capable, even, of expressing a palpable mood, from an ambivalent monosyllabic remark to a louder progression of various phrases that would imply exacerbation. Or excitement. As though in response to the artist’s various statements in various languages, the animal’s passion grows hysterically, proving again and again its ability to respond, its ability to answer, its ability to resist being reduced to a concept.

Graham Harman’s essay, “Badiou’s Horses and Baudelaire’s Cats” looks at two examples of animal representation. First, he looks at Badiou’s discussion of ancient horse-paintings in the Chauvet cave to explore the relationship between material individuals and the concepts with which they correspond. “What guides Badiou’s theory of art, like his theory of everything else,” Harman writes, “is an empirical diversity of individuals on the one hand and the intelligent paradigm of the idea on the other.”[10] According to Badiou, each empirical horse points back to the fundamental archetype with which it participates, and the best works of art depicting horses would not only “contain the universal form” of the horse, but also “[teach] us something about horses as a biological type.”[11]

If Christ is God-become-man, then Badiou’s horses are idea-become-image, and all horse-paintings participate in the same idea of horseness.[12]

As a counterpoint to this Platonic arrangement, Harman plays with translations of Baudelaire poems, especially “Cats” from Les Fleurs du mal.

Dozing, all cats assume the svelte design

of desert sphinxes sprawled in solitude,

apparently transfixed by endless dreams;

their teeming loins are rich in magic sparks,

and golden specks like infinitesimal sand

glisten in those enigmatic eyes.[13]

Although, Baudelaire relies upon “cats” as a recognizable group (as Derrida notes[14]), Harman shows that Baudelaire’s poem only works because of its ability to slip between a universal concept, Cat, and the individual cat-subject of the poem. “If anything, Baudelaire is drawing on our familiarity with cats to enable him to leave certain things unsaid.”[15] Harman interrogates the specificity of the cat in question through a process of word substitutions; by replacing “cats” with “moose” for instance, and “svelte” for “thirsty,” he demonstrates that the poem’s power relies on its capacity to conjure a specific cat in the mind of a reader. This cat participates in a recognizable genre of cat-ness while distinguishing itself from that category. The cat is general and specific, known and unknown, familiar but strange.

Art goes beyond empirical individuals by producing aesthetic individuals, not by teaching us about invariants that transcend all individuals.[16]

Larger consequences unfold by this same logic, for not only do we recognize Little Grey flicker — like Derrida’s cat — in and out of specificity, the world she bears flickers as well. The prospect of her autonomous consciousness surfaces in discrete moments — the sprawl of her solitude, for instance, or the enigmatic eyes Baudelaire is so fond of — and only through these postures does one glimpse an inner life. Furthermore, if this cat exists somehow between the universal and singular, if she harbors a discrete and individuated world running parallel to mine or Bloom’s, so additional worlds begin to encroach upon one’s awareness — those of other cats, yes, but then why not horses, parakeets, whales, jellyfish, termites, perhaps even computers, and more inert materials like drones, plastics, oil, and so on? An infinite number of worlds become theoretically possible, each interlocking and entwined, worlds that remain autonomous, reciprocal though exclusive, with their own internal logics, agendas, and languages, many of which periodically intersect the human sphere.

Broodthaers’ cat is and is not a readymade. Like a readymade it is strange, perhaps also like a readymade it is exploited for its capacity to elicit a strange feeling. To the human in the recording, the cat is presented as an aesthetic tool. Yet the listener cannot dismiss the cat’s individual existence. Its unique voice disallows the cat to become, simply, a sign of its species, locating the cat’s body and will as a resonant material presence that the listener can neither access completely nor deny. The cat’s double function — an artistic foil and an individual feline being — reflects Broodthaers’ select phrases: This is a pipe. This is not a pipe. The pipe is and is not itself. The cat is and is not itself. The listener can never entirely apprehend either the pipe or the cat.

I think of a Pallas Cat video that went viral a few years ago. Though endangered, Pallas cats exist in Central Asia, living primarily around 14,000 ft. above sea level. Unlike most cats, they have round pupils. They are intensely solitary, near threatened on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, having been discovered by accident in 1776 by a German naturalist, Peter Simon Pallas. Although he gave them a proper name, Otocolobus manu, the breed is generally addressed by his family name. In the July 2014 video, a Pallas cat discovers a secret camera hidden just outside of its den. It stares at the camera — us — hiding ever so slightly behind the rocky entrance of its home. I wonder what it sees — a strange, perfectly circular, dark, reflective surface. The cat sits up suddenly, noticing perhaps that the camera’s reflection also changes. The animal approaches, quickly now, with direct authority, trotting just out of view, as though recognizing the camera’s limited peripheral vision. Then suddenly — like the Ninja Cat — Pallas’s face pops up, engulfing the frame of the camera, so close as to be out of focus, one green eye staring very seriously into the robotic, alien lens. It is looking at us. Perhaps its sees its own reflection, perhaps also the robotic contractions of the automatic camera adjusting to changes in light. Meanwhile, the cat’s blurred face obliterates the rest of the landscape, as it sniffs, and blinks intelligently — its own pupils expand — and it drops down, again out of view. We hear the soft crunch of its feet walking away; birds in the background carry on.

Imagine the crowd in Minneapolis.

Months ago and shortly after moving to a new apartment, I woke up in the middle of the night when I thought I heard my husband snoring. It was pitch black. I had no idea what time it was and foggily recalled the surrounding apartment. The most articulated presence came as a wheezing sound, unusually high pitched and light. Like a baby crying in another part of the apartment building, except that it seemed so near at hand. Devin must be having a bad dream, I thought, and moved to wake him, stopping short when I realized he wasn’t making any noise. Rather, the sound came from elsewhere in the room. The hair on my arms rose. My heart began to hammer. Then, I decided it must be Little Grey. But she was so loud for a cat, and too human-sounding. I’d never heard her snore before and I wasn’t familiar enough with our surroundings to work out where exactly where she was sleeping. Yet it was her, and her voice emerged from the shared, half-conscious night.

In book ten of the Odyssey, Odysseus visits the island of Circe and half of his men eat her food, fall under her spell, and become swine. Having stayed behind with the ships, Odysseus escapes the same fate and is therefore called to the rescue; he gets a special root from Hermes (“moly”) that will make him immune to Circe’s enchantment. When she realizes her powers are ineffective — “you must be spell-proof,” she says — they go to bed and Circe restores his men to human form thereafter. Although beastliness is traditionally associated with immoral domination, appetite, stupidity, or violence, I wonder if the monstrous transformation in this section isn’t more complex. Odysseus’ ability to resist Circe’s spell (courtesy of the gods’ botanical science) enables a friendship solidified with sex. “‘…sheathe your sword and let us go to bed, that we may make friends and learn to trust each other.’” If an erotic encounter restores the crew’s humanity, perhaps the problematic category of animal refers primarily to the alien character of the men—as though they become strange when newly contextualized by Circe’s environment. The Circe Section of Ulysses takes place in the red light district of Nighttown. Because the chapter is written in the form of a play, the reader activates the text like a spell, making the narrative come to life through her own mouth and mind (she is thus implicated as one becoming enchanted and enchanting) as it slips between dream and wakefulness, sexual provocation, politics, and a constellation of symbols. The section begins with Stephen’s perspective and then becomes Bloom’s via the memory of his dead father and mother, encounters with characters, and the fantasy of his estranged wife, Molly. Beyond the sexual charge permeating both iterations of Circe’s world, I suggest that the metaphorical “animals” the humans become is less a reflection of beastly-ness in the human subject and more the sign of a human subject responding to an otherness so profound as to undermine the conviction of their own human identity. The pig-ness of Odysseus’ men is rather superficial — “They were like pigs — head, hair, and all, and they grunted just as pigs do; but their senses were the same as before, and they remembered everything.”[17] Yet these men thoroughly confound distinctions otherwise seen as hard and fast; an outside observer would be unable to differentiate pig from man, and thus might eat either unequivocally. Once Bloom steps outside of his habit and into the red light district, his relation to the world starts to shift. Bells and gongs have voices, (“Haltyaltyaltyall” and “Bang Bang Bla Bak Blud Bugg Bloo”). Time is similarly thrown out of whack as visions of the past overwhelm the present. The terror of the animal-concept, therefore, is its ability to trouble elaborate (and often theoretical) conventions humankind espouses as universal truths.

I cannot describe Little Grey’s actions without doubt and qualification. She is always seeming. It is as though I cannot admit what seems quite clear in my experience, namely that certainly something is understood between us, between Bloom and his cat. In public, I qualify our cat. Privately, I believe her. The world of our house is made up of three members: a cat, a man, and myself. Although we share a predominantly a human interior, organized in compliance with an exterior anthro-social architecture, the animal is always accounted for, accommodated, and observed. Relative to our human similarities, she represents that frontier of a still negotiable other-ness. Still, there is a limit to what we offer our feline roommate. She has little to say about what she eats, where she lives, and even — as an indoor cat — where she can go. These conditions further limit my ability to access who she is, for while there are times in the day when I experience something of Little Grey’s interiority, she is for the most part a remote presence.

You will hear my mother say that I am cooking for the cats. This scandalizes my mother who is Levinasian without knowing it, given that my cats do not cook for me, but that’s not correct. This unequal division occurs only when I keep them in an exclusively human home, to which they adapt out of politeness. As soon as they have a home of their own, a piece of earth and of world, they cook for me. Then it’s my turn to adapt to their cooking of birds and little rodents.[18]

Broodthaers’ interview engages in a call and response; the meaning he attempts to ascribe through French and English is irrelevant in a way, for what he does instead is open the possibility of language to incorporate the illogic of other creatures. Whatever else we may say, the cat answers, differently and consistently. Broodthaers also answers the cat. A conversation develops that both constituents contribute to, shape and form collaboratively.

In a 2007, Art Orienté object (AOo), the French collaborative group comprised of Marion Laval-Jeantet and Benoît Mangin, began a series of body modification experiments intended to communicate with animals outside of language. “Basically the project was to artistically adapt Jacob von Uexküll’s Umwelt theory, which argues that the meaning of an environment differs from one animal to another in relation to its sensorial system.”[19] Instead of trying to teach an animal human language, AOo tried to adapt and incorporate animal expressions. This notion was originally inspired in 1993 by a studio cat, whom Laval-Jeantet describes as a magnificent, self-absorbed presence. “Hadji was like a stallion, who spent several hours each day pacing up and down our studio, like a wild beast in a cage, following a path defined by himself. We then made a kind of game, in which we would add an obstacle to each of his circular trajectories.”[20] They documented the cat negotiating its changing landscape in a video. “The changes were imperceptible and the viewer, who could not see what we were doing in the video, didn’t realize that each of the cat’s episodic hesitations resulted in him being forced to change his itinerary. So, it is the Umwelt of the cat revealed the Umwelt of the artist.”[21] This first experiment led to others, during which AOo tried to produce works that modified their perception of cats.

Over the years, we made many ethological experiments with [cats], but it seemed that we were stuck in the same place in their hierarchy. That’s when the idea occurred to me to become digitigrade. A kind of fantasy where I would be able to jump onto the table in a single leap with paws that were too long…I drew the “cat shoes,” which the prosthetist made. As soon as I put them on and got used to this strange way of walking, the cats came up to me, sniffed and jumped on me, playing with me in the same way as they played between themselves.

For the resulting 2007 work, Felinanthropy, the artists created prosthetic legs that allowed the human to walk about on all fours, and thus share the physical stature of a cat. “The artist object [prosthetics] worked, it had moved my role in [to] the feline, domestic hierarchy.”[22] By changing her status as a bi-ped, Laval-Jeantet transformed her relationship to cats, who, according to the artist, no longer recognized her explicitly as human, but rather as some in-between-creature that shared both human and cat qualities.

More recently, Laval-Jeantet built up an immunity to horse plasma over the course of a year, and in 2012, enacted a temporary horse plasma transplant for a live audience; this they called May the Horse Live in Me. Prosthetics were another major component to this performance as well; at the end of the transfusion, Laval-Jeantet put on a pair of stilts made to look and move like a horse’s hind legs, and walked around the performance space with a living horse. These curious attempts to access nonhuman experience only serve to highlight the strange and perfect inaccessibility of nonhuman realms, at once problematizing our traditional engagement with nature as a picturesque field, and further entrenching humankind within it.

The stilts were mostly there to allow me a different way of communicating with the horse who was present during the performance. I was a little afraid of horses, actually. And it seems like horses’ attitudes change completely when your eyes are at the same height as theirs. With the stilts, my eyes were the same height as his, and I could see that the horse was calmer. It was also a way for me to be aware of the reversal of roles between me and the animal. And naturally, it was a way to distract myself from the possible anxiety that might arise because of the infusion. Because I was on stilts, I could only think of the goal: to join with the animal, and not of the psychological problems that might come out during the performance. Experiments with prosthetics always affect your fears about your body, and in the performance it was necessary that I have a strong sense of a double transformation, mental and biological.[23]

In a 2014 video from the Walker Art Center cat fancy program, a black cat hangs out of an apartment window, barking. It sounds like a toy dog, it voice high and sharp like a terrier. In the midst of a long succession of barks, the cat turns to see the camera. It appears to change its mind and the bark it is in the middle of pronouncing ends in a meow. Every subsequent sound it makes is a meowing. The video is called “Cat gets caught barking by human and resumes meowing.” Does that cat’s reaction reflect some kind of shame or self-consciousness?

So much of humanity’s self-definition comes from language. The earliest form of writing is used to mark humankind’s advancement as the definitive turn at which humans began to differentiate itself as a species. Nonhumans are automatically excluded from that history not only because their respective inabilities exclude them from conversing in human languages but also because their worldviews do not necessarily fit to human reason. This is not to say that other species do not communicate or possess some consciousness of their own, but that their modes of communication are so ill-fitted to the structure of human discourse as to appear unreasonable and chaotic when compared. Yet the world teems with such complexity, it seems remarkable that it holds together as a unified, albeit inaccessible whole.

As a landmark of modernity, Ulysses’ narrative stretches the capacity of language to include the possibility of realities explicitly excluded by human language. The cat speaks without apparent meaning. Contextualized, however, the gibberish of the cat becomes meaningful, pointing at something just out of reach. Broodthaers accomplishes a similar kind of pointing, juxtaposing the language of human art with the language of his cat. What is similarly unsettling, is the way Broodthaers’ cat seems likewise meaningful and self-directed, even if we cannot relate to (or anticipate) its intentions; there is an echo of kinship in their encounter. AOo’s sculptural props become souvenirs of their hybrid dalliance while offering a literal representation of material and identity exchange. A kind of theoretical rebellion occurs — one in which the human, like any and all other life forms, is negotiating an unfixed, “mesh” of interdependent species, materials, and genomes. Bloom encounters the cat’s autonomy of perception, a perception in which he is but a subject, becoming more aware of himself and unsettled in that awareness. By supplying the cat with its own specter of language, by providing room for its textual response, Joyce cracks the door on a world Bloom will never access. We feel its presence and integrity, while being unable to enter and know it first hand — like noticing water in the bottom of a boat in dream.

Leaks begin to spring up all over the place, as the boat’s integrity is called further into question. We feel the presence of the ocean beneath our feet, feel its teeming, impossibility against our own tenuous scaffold of reason. By admitting one cat, we must acknowledge that throng of many. We must acknowledge the strange porous bounds of our own selves. Bloom—the textual human—faces the limit of his anthropocentric perspective, while wondering after the cat’s thoughts. Despite the inaccessibility of nonhuman worlds, the art object (the prosthetic limbs of a cat, the readymade, or fiction of Ulysses) create a theoretical bridge for awareness that extends outside of the rational human view, disrupting a hierarchical order, as we catch a glimpse of the more fluid ecological tapestry in which humanity is integrated.

Strangers applaud.

You see them smiling in the dark.

The flash of their teeth in light —

laughing.

NOTES:

[1] “More than 48,000 people have subscribed to Maru’s YouTube channel and more than 46 million views have been generated by cat lovers and Maru’s fans from all over the world.”Amy Bajalis, “Interview with Maru the Cat,” Love Meow, accessed January 21, 2015. http://lovemeow.com/2010/04/interview-with-maru-the-cat/#JOz5YiAL8q4zbRIh.99

[2] James Joyce, Ulysses, (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1961) 55.

[3] Jacques Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am, trans. David Wills, (Bronx, NY: Fordham University Press, 2008) 9.

[4] Ibid., 25.

[5] Ibid., 8.

[6] Shannon Stratton (artist, curator), Restless: A Visual Essay, The Green Lantern Gallery, Chicago, 2008.

[7] There is one other instance in Numbers 22:28; a Donkey replies to Balaam when struck with a stick.

[8] Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am, 42.

[9] Marcel Broodthaers, “Interview with a Cat,” Youtube, April 2010, accessed September 5, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFuHPOMKmt4

[10] Graham Harman, “Badiou’s Horses and Baudelaire’s Cats,” in Ghost Nature, ed. Caroline Picard, (Chicago, IL: The Green Lantern Press, 2014) 38.

[11] Ibid., 38.

[12] Ibid., 38.

[13] Charles Baudelaire, Les Fleures du mal, trans. R. Howard (Boston: Godine, 1982). Quoted by Harman, “Badiou’s Horses and Baudelaire’s Cats,” 39.

[14] “No, no, my cat…does not appear here to represent, like an ambassador, the immense symbolic responsibility with which our culture has always charged the feline race…from Baudelaire to Rilke, Buber and many others.” Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am, 9.

[15] Harman, “Badiou’s Horses and Baudelaire’s Cats,” 43.

[16] Harman, “Badiou’s Horses and Baudelaire’s Cats,” 43.

[17] Homer, The Odyssey, trans. Samuel Butler, (London: Longmans, Greens and Co., 1900) 130.

[18] Hélène Cixous and Peggy Kamuf, “The Keys To: Jacques Derrida as Proteus Unbound,” in Discourse, Vol. 30, No ½, Special Issue: “Who?” or “What?” —Jacques Derrica, (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2008) 94.

[19] Marion Laval-Jeantet, “Self-Animality,” Plastik: Art and Science, June 2011, accessed January 6, 2014,

http://art-science.univ-paris1.fr/plastik/document.php?id=559.

[20] Laval-Jeantet, “Self-Animality.”

[21] Laval-Jeantet, “Self-Animality.”

[22] Laval-Jeantet, “Self-Animality.”

[23] Marion Laval-Jeantet, “Adapting the Umwelt: Art Orienté objet,” interviewed by Caroline Picard, Bad at Sports, August 22, 2016, accessed August 22, 2016, http://badatsports.com/2016/adapting-the-umwelt-art-oriente-objet/.

_____________________

Bibliography

Bajalis, Amy. “Interview with Maru the Cat,” Love Meow, accessed January 21, 2015.

http://lovemeow.com/2010/04/interview-with-maru-the-cat/#JOz5YiAL8q4zbRIh.99

Broodthaers, Marcel. “Interview with a Cat,” Düsseldorf, Germany: Museum of Modern Art,

- Published on Youtube, April 2010. Accessed September 5, 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFuHPOMKmt4

Cixous, Hélène and Kamuf, Peggy. “The Keys To: Jacques Derrida as Proteus Unbound,”

Discourse, Vol. 30, No ½, Special Issue: “Who?” or “What?” —Jacques Derrida. 71-122.

Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2008.

Derrida, Jacques. The Animal That Therefore I Am, trans. David Wills. Bronx, NY: Fordham

University Press, 2008.

Harman, Graham. “Badiou’s Horses and Baudelaire’s Cats.” In Ghost Nature, edited by Caroline

Picard, 33-43. Chicago, IL: The Green Lantern Press, 2014.

Homer. The Odyssey, translated by Samuel Butler. London: Longmans, Greens and Co., 1900.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1961.

Laval-Jeantet, Marion. “Self-Animality,” Plastik: Art and Science, June 2011. Accessed

January 6, 2014. http://art-science.univ-paris1.fr/plastik/document.php?id=559.

Laval-Jeantet, Marion. “Adapting the Umwelt: Art Orienté objet,” interviewed by Caroline Picard,

Bad at Sports, August 22, 2016. Accessed August 22, 2016.

http://badatsports.com/2016/adapting-the-umwelt-art-oriente-objet/.

________________________

Hyperallergic writes, “The essays in Aesthetics Equals Politics make the case for a reignited understanding of aesthetics—one that casts aesthetics not as illusory, subjective, or superficial, but as a more encompassing framework for human activity. Such an aesthetics, the contributors suggest, could become the primary discourse for political and social engagement. Departing from the “critical” stance of twentieth-century artists and theorists who embraced a counter-aesthetic framework for political engagement, this book documents how a broader understanding of aesthetics can offer insights into our relationships not only with objects, spaces, environments, and ecologies, but also with each other and the political structures in which we are all enmeshed.”